剑桥雅思5:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题+答案+解析

发布时间:2020-09-11 关键词:剑桥雅思5:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题+答案+解析剑桥雅思5:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14- -26, which are based on Reading Passage 2below.

Nature or Nurture?

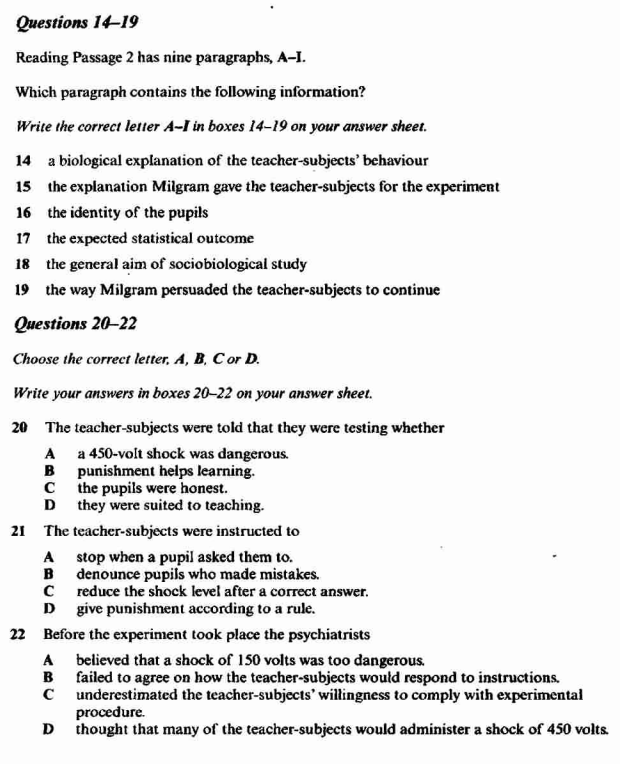

A few years ago, in one of the most fascinating and disturbing experiments in behaviouralpsychology, Stanley Milgram of Yale Universily tested 40 subjects from ail walks of life fortheir willingness to obey instructions given by a "leader' in a situation in which the subjectsmight feel a personai distaste for the actions they were called upon to perform. Specifically,Milgram told each volunteer 'teacher-subject' that the experiment was in the noble cause ofeducation, and was designed to test whether or not punishing pupils for their mistakes

would have a positive effect on the pupils' ability to learn.

Milgram's experimental set-up involved placing the teacher-subject before a panel of thirtyswitches with labels ranging from '15 volts of electricity (slight shock)' to '450 volts

(danger - severe shock)' in steps of 15 volts each. The teacher-subject was told that

whenever the pupil gave the wrong answer to a question, a shock was to be administered,beginning at the lowest level and increasing in severity with each successive wrong

answer. The supposed 'pupil' was in reality an actor hired by Milgram to simulate receivingthe shocks by emitting a spectrum ol groans. screams and writhings together with an

assortment of statements and expletives denouncing both the experiment and the

experimenter. Milgram told the teacher-subject to ignore the reactions of the pupil, and toadminister whatever level of shock was calied for, as per the rule governing the

experimenta! situation of the moment.

As the experiment unlolded, the pupil wouid deliberately give the wrong answers to

questions posed by the teacher, thereby bringing on various electrical punishments, evenup to the danger level of 300 volts and beyond. Many of the teacher-subjects balked atadministering the higher levels of punishment, and turned to Milgram with questioninglocks and/or complaints about continuing the experiment. In these situations, Milgramcalmly explained that the teacher-subject was to ignore the pupil's cries for mercy and

carry on with the experiment. If the subject was still reluctant to proceed, Milgram said thatit was important for the sake of the experiment that the procedure be followed through tothe end. His final argument was, You have no other choice. You must go on.' What Migramwas trying to discover was the number of teacher-subjects who would be willing to

administer the highest levels of shock, even in the face of strong persona! and moralrevulsion against the rules and conditions of the experiment.

Prior to carrying out the experiment, Milgram explained his idea to a group of

39 psychiatrists and asked them to predict the average percentage of people in an

ordinary population who would be willig to administer the highest shock level of 450 volts.The overwhelming consensus was that virtually all the teacher-subjects would refuse toobey the experimenter. The psychiatrists felt that 'most subjects would not go beyond150 volts'" and they further anticipated that only four per cent would go up to 300 volts.

Furthermore, they thought that only a lunatic fringe of about one in 1,000 would give thehighest shock of 450 volts.

What were the actual results? Well, over 60 per cent of the teacher-subjects continued toobey Milgram up to the 450-volt limit! In repetitions of the experiment in other countries, thepercentage of obedient teacher-subjects was even higher, reaching 85 per cent in one

country. How can we possibly account for this vast discrepancy between what calm,

rational, knowledgeable people predict in the comfort of their study and what pressured,flustered, but cooperative 'teachers' actually do in the laboratory of rea life?

One's first inclination might be to argue that there must be some sort of built-in animalaggression instinct that was activated by the experiment, and that Milgram's teacher-

subjects were just following a genetic need to discharge this pent-up primal urge onto thepupil by administering the electrical shock. A modern hard-core sociobiologist might evengo so far as to claim that this aggressive instinct evolved as an advantageous trait, havingbeen of survival value to our ancestors in their struggle against the hardships of life on theplains and in the caves, ultimately finding its way into our genetic make-up as a remnant ofour ancient animal ways.

An alternative to this notion ot genetic programming is to see the teacher subjects' actionsas a result of the social environment under which the experiment was carried out. As

Milgram himself pointed out, 'Most subjects in the experiment see their behaviour in alarger context that is benevolent and useful to society - the pursuit of scientific truth. Thepsychological laboratory has a strong claim to legitimacy and evokes trust and confidencein those who perform there. An action such as shocking a victim, which in isolation appearsevil, acquires a completely different meaning when placed in this setting.'

Thus, in this explanation the subject merges his unique personality and personal and moralcode with that of larger institutional structures, surrendering individual properties like

loyalty, self- sacrifice and discipline to the service of malevolent systems of authority.

Here we have two radically different explanations for why so many teacher-subjects wereiling to forgo their sense of personal responsibility for the sake of an institutional authorityfigure. The problem for biologists, psychologists and anthropologists is to sort out which ofthese two polar explanations is more plausible. This, in essence, is the problem of modernsociobiology - to discover the degree to which hard-wired genetic programming dictates,or at least strongly biases, the interaction of animals and humans with their environment,that is, their behaviour. Put another way, sociobiology is concerned with elucidating thebiological basis of all behaviour。

阅读第二篇

你应该花大约20分钟在14-26的问题上,这些问题是基于下面的阅读通道2.

天生还是后天?

几年前,耶鲁大学(Yale University)的斯坦利·米尔格拉姆(Stanley Milgram)是行为心理学中最引人入胜和最令人不安的实验之一。他对来自各行各业的40名受试者进行了测试,测试他们是否愿意服从“”的指示,在这种情况下,被试可能会对自己被要求做的行为感到个人厌恶。具体来说,米尔格拉姆告诉每个志愿者“教师-受试者”,该实验属于崇高的教育事业,其目的是检验是否惩罚学生犯错误。

会对学生的学习能力产生积极的影响。

米尔格拉姆的实验装置包括将教师置于一块30伏开关的面板前,标签从“15伏特(轻微电击)”到“450伏特”不等。

(危险-严重休克)每步15伏特。老师被告知

每当学生对一个问题给出错误的答案时,就要进行电击,从水平开始,每次错误越严重,越严重。

回答。这个所谓的“学生”实际上是米尔格拉姆雇来的演员,他通过发出光谱呻吟来模拟受到击。尖叫和扭动在一起

各种各样的声明和咒骂,既谴责实验,又谴责

实验者。米尔格拉姆对老师说,不管学生的反应如何,都要无视他们的反应,并按照有关的规则来管理任何程度的震惊。

实验!目前的情况。

随着实验的展开,这个学生会故意给出错误的答案。

老师提出的问题,从而造成各种惩罚,甚至达到300伏特以上的危险程度。许多教师在这种情况下,米尔格拉姆平静地解释说,教师的主题是忽视学生的求饶和求饶。

继续做实验。如果研究对象仍然不愿继续下去,米尔格拉姆说,为了实验的目的,这是很重要的,因为这个过程要一直进行到最后。他最后的论点是,你别无选择。你必须继续。“米格拉姆想要发现的是,有多少教师-科目-愿意

管理最别的震惊,即使面对强大的人格!违背实验的规则和条件。

在进行实验之前,米尔格拉姆向一群人解释了他的想法。

39名精神病医生要求他们预测

普通民众中,威格将执行450伏特的电击水平。压倒性的共识是,几乎所有的教师科目都会拒绝服从实验者。精神病学家认为,“大多数受试者不会超过150伏特”,他们进一步预测只有4%的人能达到300伏特。

此外,他们还认为,只有1/1000左右的疯狂边缘才能产生450伏特的击。

实际结果是什么?嗯,超过百分之六十的教师-科目继续服从米尔格拉姆,直到450伏特的极限!在其他的重复实验中,听课教师的比例更高,达到85%。

。我们怎么能解释这种平静之间的巨大差异,

理性的,知识渊博的人预测他们学习的舒适感,以及在现实生活的实验室里老师们到底做了什么压力,慌乱,但合作的“老师”呢?

一个人的个倾向可能是争辩说,有某种内在的动物攻击本能被实验激活了,而米尔格拉姆的老师-

受试者只是遵循一种遗传需要,通过施加电击将这种压抑的原始动释放到瞳孔上。一位现代的铁杆社会生物学家可能会声称,这种侵略性的本能进化为一种有利的特质,对我们的祖先在平原和洞穴中与生活的艰辛作斗争中具有生存价值,最终找到了作为我们古老动物方式的残余的基因组成。

另一种替代遗传编程概念的方法是看到教师的行为,这是实验所处的社会环境的结果。如

米尔格拉姆本人指出:“实验中的大多数受试者都认为自己的行为是善意的,对社会是有益的--追求科学真理。心理实验室对合法性有很强的要求,并在那里的执行者身上唤起了信任和信任。在这种环境中,像震惊受害者这样的行为,在孤立的情况下,有着完全不同的含义。”

因此,在这一解释中,主体将他独特的人格、个人和道德准则与更大的制度结构融合在一起,交出个人财产,如

忠诚,自我牺牲和纪律,为邪恶的权威系统服务。

在这里,我们有两个完全不同的解释,为什么如此多的教师-科目放弃他们的个人责任感,为了一个机构的权威人物。对于生物学家、心理学家和人类学家来说,问题在于找出这两种极地解释中哪一种更可信。从本质上讲,这就是现代社会生物学的问题--去发现硬基因编程在多大程度上决定了动物和人类与环境的互动,即他们的行为,或者至少是强烈的偏见。换句话说,社会生物学关注的是阐明所有行为的生物学基础。

剑桥雅思5:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题及答案解析

剑桥雅思5:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2答案解析