剑桥雅思7阅读:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题+答案+解析

发布时间:2020-11-17 关键词:剑桥雅思7阅读:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题+答案+解析为帮助同学们学习,小编为大家整理了剑桥雅思7阅读:Test1雅思阅读PASSAGE 2真题+答案+解析,希望能够对大家有帮助。关于剑桥雅思的资讯关注新航道北京学校剑桥雅思栏目。

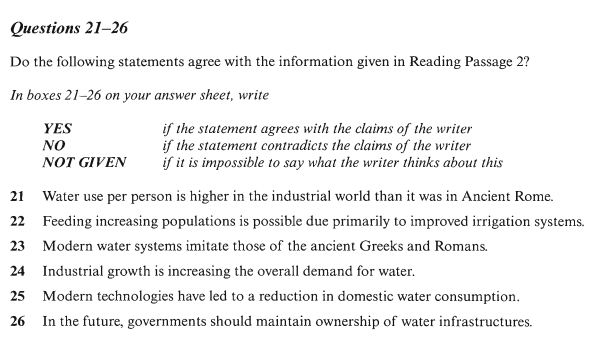

MAKINGi_ EVERYDROP COUNT

The history of human civilisation is entwined with the history of the ways we havelearned to manipulate water resources. As towns gradually expanded, water wasbrought from increasingly remote sources, leading to sophisticated engineering

efforts such as dams and aqueducts. At the height of the Roman Empire, nine majorsystems, with an innovative layout of pipes and well-built sewers, supplied the

occupants of Rome with as much water per person as is provided in many parts ofthe industrial world today.

During the industrial revolution and population explosion of the 19th and 20th

centuries, the demand for water rose dramatically. Unprecedented construction oftens of thousands of monumental engineering projects designed to control floods,protect clean water supplies, and provide water for irrigation and hydropower

brought great benefits to hundreds of millions of people. Food production has keptpace with soaring populations mainly because of the expansion of artificial irrigationsystems that make possible the growth of 40 % of the world's food. Nearly one fifthof all the electricity generated worldwide is produced by turbines spun by the powerof falling water.

Yet there is a dark side to this picture: despite our progress, half of the world's

population still suffers, with water services inferior to those available to the ancientGreeks and Romans. As the United Nations report on access to water reiterated inNovember 2001, more than one billion people lack access to clean drinking water;some two and a half billion do not have adequate sanitation services. Preventablewater-related diseases kill an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 children every day, andthe latest evidence suggests that we are falling behind in efforts to solve theseproblems.

The consequences of our water policies extend beyond jeopardising human health.Tens of millions of people have been forced to move from their homes - often withlitt warning or compensation - to make way for the reservoirs behind dams. Morethan 20 % of all freshwater fish species are now threatened or endangered becausedams and water withdrawals have destroyed the free-flowing river ecosystems

where they thrive. Certain irrigation practices degrade soil quality and reduce

agricultural productivity. Groundwater aquifers* are being pumped down faster thanthey are naturally replenished in parts of India, China, the USA and elsewhere. Anddisputes over shared water resources have led to violence and continue to raiselocal, national and even international tensions.

At the outset of the new millennium, however, the way resource planners think aboutwater is beginning to change. The focus is slowly shifting back to the provision ofbasic human and environmental needs as top priority - ensuring 'some for all,'instead of 'more for some'. Some water experts are now demanding that existinginfrastructure be used in smarter ways rather than building new facilities, which isincreasingly considered the option of last, not first, resort. This shift in philosophyhas not been universally accepted, and it comes with strong opposition from someestablished water organisations. Nevertheless, it may be the only way to addresssuccessfully the pressing problems of providing everyone with clean water to drink,adequate water to grow food and a life free from preventable water-related illness.Fortunately - and unexpectedly - the demand for water is not rising as rapidly assome predicted. As a result, the pressure to build new water infrastructures hasdiminished over the past two decades. Although population, industrial output andeconomic productivity have continued to soar in developed nations, the rate atwhich people withdraw water from aquifers, rivers and lakes has slowed. And in afew parts of the world, demand has actually fallen.

What explains this remarkable turn of events? Two factors: people have figured outhow to use water more efficiently, and communities are rethinking their priorities forwater use. Throughout the first three-quarters of the 20th century, the quantity offreshwater consumed per person doubled on average; in the USA, water

withdrawals increased tenfold while the population quadrupled. But since 1980, theamount of water consumed per person has actually decreased, thanks to a range ofnew technologies that help to conserve water in homes and industry. In 1965, forinstance, Japan used approximately 13 million gallons* of water to produce $1

million of commercial output; by 1989 this had dropped to 3.5 million gallons (evenaccounting for inflation) - almost a quadrupling of water productivity. In the USA,water withdrawals have fallen by more than 20 % from their peak in 1980.

On the other hand, dams, aqueducts and other kinds of infrastructure will still haveto be built, particularly in developing countries where basic human needs have notbeen met. But such projects must be built to higher specifications and with moreaccountability to local people and their environment than in the past. And even inregions where new projects seem warranted, we must find ways to meet demandswith fewer resources, respecting ecological criteria and to a smaller budget.

MAKINGi_ EVERYDROP COUNT

人类文明史与我们掌握的操纵水资源的方法的历史交织在一起。随着城镇的逐渐扩张,人们只能从越来越偏远的地方取水,由此产生了复杂的水利工程

比如建造水坝和引水渠。在罗马帝国的鼎盛时期,九个主要的下水道系统,以创新的管道布局和建造良好的下水道系统提供了下水道

罗马居民的人均用水量相当于当今工业世界的许多地区的人均用水量。

在19世纪和20世纪的工业革命和人口爆炸时期

几个世纪以来,对水的需求急剧上升。为了控制洪水、保护清洁水源、灌溉和水力发电,中国地建设了数以万计的大型工程项目

给亿万人民带来了巨大的利益。由于人工灌溉系统的扩大,粮食生产一直与人口猛增保持同步,这使得世界粮食产量的40%得以增长。世界上近五分之一的电力是由瀑布带动的涡轮机产生的。

然而,这幅图景也有阴暗的一面:尽管我们取得了进步,但却占了世界的一半

人口仍在受苦,供水服务不如古代希腊人和罗马人。正如2001年11月联合国关于获得水的报告重申的那样,超过10亿人无法获得清洁饮用水;大约25亿人没有足够的卫生服务。据估计,每天有1万到2万儿童死于可预防的与水有关的疾病。证据表明,我们在解决这些问题方面的努力还远远落后。

我们的水资源政策的后果不仅仅是危害人类健康。为了给大坝后面的水库让路,数千万人被迫搬离家园,而且往往没有得到任何警告或补偿。超过20%的淡水鱼品种现在受到威胁或濒临灭绝,因为山洪和取水破坏了自由流动的河流生态系统

他们茁壮成长。某些灌溉措施会降低土壤质量和减少土壤质量

农业生产力。在印度、中国、美国和其他一些地区,地下水含水层被抽取的速度比自然补充的速度要快。关于共享水资源的争端已经导致暴力,并继续地区、甚至国际紧张局势。

然而,在新千年之初,资源规划者对水资源的看法开始发生变化。重点正在慢慢地转移到提供基本的人类和环境需求作为首要任务——确保“有一部分人享有”,而不是“有一部分人享有”。一些水务现在要求以更明智的方式利用现有的基础设施,而不是建造新的设施。建造新设施越来越被认为是最后而不是首先的选择。这种哲学上的转变并没有被普遍接受,而且遭到了一些老牌水务组织的强烈反对。然而,它可能是成功解决紧迫问题的途径,这些问题包括为人人提供清洁饮水、充足的水种植粮食以及使生活免受可预防的与水有关的疾病。幸运的是,出乎意料的是,对水的需求并没有像一些人预测的那样增长。因此,在过去20年里,建设新的供水基础设施的压力已经减少。尽管发达的人口、工业产出和经济生产率持续飙升,但人们从含水层、河流和湖泊取水的速度已经放缓。在世界上的一些地区,需求实际上已经下降。

如何解释这一引人注目的转变?两个因素:人们已经找到了更有效地用水的方法,社区正在重新考虑他们用水的优先次序。在20世纪的前四分之三年中,人均淡水消耗量翻了一番;在美国,水

取款量增加了十倍,而人口则增加了四倍。但自1980年以来,由于一系列有助于家庭和工业节水的新技术,人均用水量实际上有所下降。例如,1965年,日本大约使用1300万加仑的水生产1美元

百万商业产值;到1989年,这一数字下降到350万加仑(甚至考虑到通货膨胀)——几乎是水生产力的四倍。在美国,取水量从1980年的峰值下降了20%以上。

另一方面,大坝、渡槽和其他类型的基础设施仍将需要建造,特别是在人类基本需求没有得到满足的发展中。但这样的项目必须建造更高的规格和的使用